Basics of LOD

Part 1

Working with Building Information Modeling, BIM, does not only mean using new technologies and processes; there are also a lot of new terminologies to deal with. Unfortunately many of these new terms are not easy to understand and many seem to have changed their meaning over the years. One example is LOD. This is one of the earliest BIM acronyms that have been created. It is used in BIM projects worldwide, but there are still many misunderstandings and abuses of the concept.

That’s why we are launching a series on our blog, exploring some of the basic concepts of LOD and giving practical guidance on how to apply them correctly in practice. The first part is about the basics of LOD.

LOD stands for “Level of Development”. There are some variations in different countries, including the terms “level of definition” and “level of detail”, but the “level of development” is the most commonly used today. A good overview of the history of LOD and the different permutations is given by Dr. Marzia Bolpagni in her article published in 2016 «The Many Faces of LOD».

The series at a glance

- Part 1: Basics of LOD

- Part 2: Features of the LOD specification

- Part 3: ISO 19650 for the BIM planing

- Part 4: From LOD to LOIN

- Part 5: Data templates as final puzzle piece for model-based work

A question of scale

In short, LOD is a convention used to describe the level of detail or maturity of model elements. It can be useful to equate LOD with the term “scale”, which we know from conventional drawing production. Many countries have national CAD standards that define the information and representation levels of drawings at certain scales. For a planning office, the scale also gives a rough indication of the effort and thus also the costs required to produce certain drawings. For example, if a client asks an architect to submit all floor plans on a scale of 1:200, the architect will have a clear idea of both the final output of drawings (i.e. delivery) and the effort required by his team to produce these drawings. On the basis of his understanding of the project and the results to be delivered, the architect can prepare a quotation for the work.

If the client were to change his mind and demand 1:20 plans instead of 1:200 plans, this would have an enormous impact on the architect’s costs. Not only is more time needed to produce the more detailed plans, but the detail itself requires a deep understanding of the construction details of the project. In summary, the benchmark is both an agreement on performance and a measure of the effort required to achieve it, and thus becomes a contractually relevant basis.

LOD essentially replaces the convention of scale for model-based work. Virtual models have no scale, as everything is modelled 1:1. However, since a maturity level must be defined and agreed upon, the LOD concept was introduced. Similar to scale, LOD is used as a contractual specification for clients to define their delivery requirements. It also serves the contractor as a rough indicator to estimate the effort and costs for the preparation of the required services.

Geometry and information

LOD refers not only to the geometric representation of a model object, but also to its information content. In model-based work the information content outweighs the geometrical content of a model. This applies both to the amount of data and the effort required to create it and to the final value for the client.

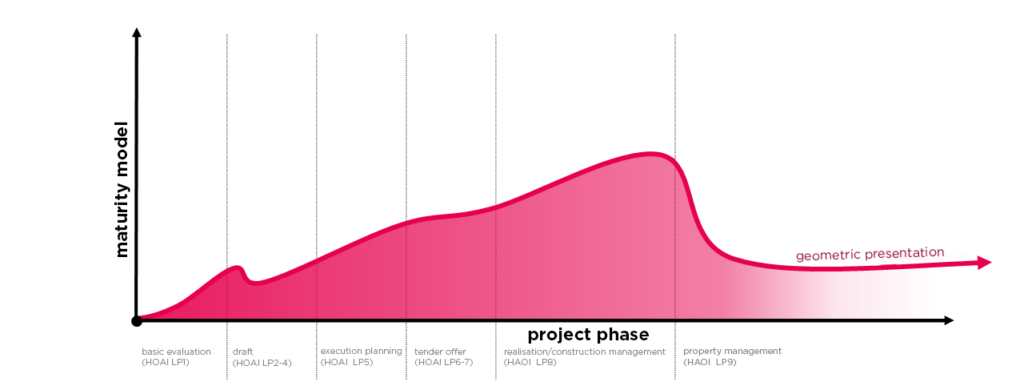

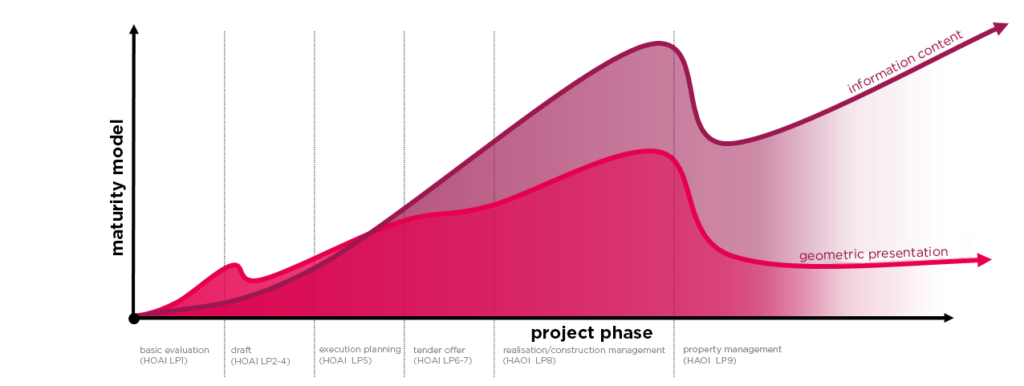

Another important consideration when creating virtual models is that geometry and information development do not always correlate directly with each other. For example, an architect can create a fairly detailed geometric model for a competition entry or for marketing visualisations at an early stage of the project, while the information content is very simple. As the design progresses, the architect can fall back on low levels of geometry to allow flexibility for design changes. This is illustrated in figure 1 below.

Typically, the geometric complexity increases in the implementation planning. This includes a possible constant height in the tender and a final climax during construction – in any case when fabrication models are required. Interestingly, most building owners do not want highly detailed building models for operation and facility management. In most cases, it is far more practical to have a simplified building model that serves as a placeholder for the more valuable property information. As a result, there is often a waste in geometric detail at project handover, which is more comparable to the design model than the detailed fabrication models.

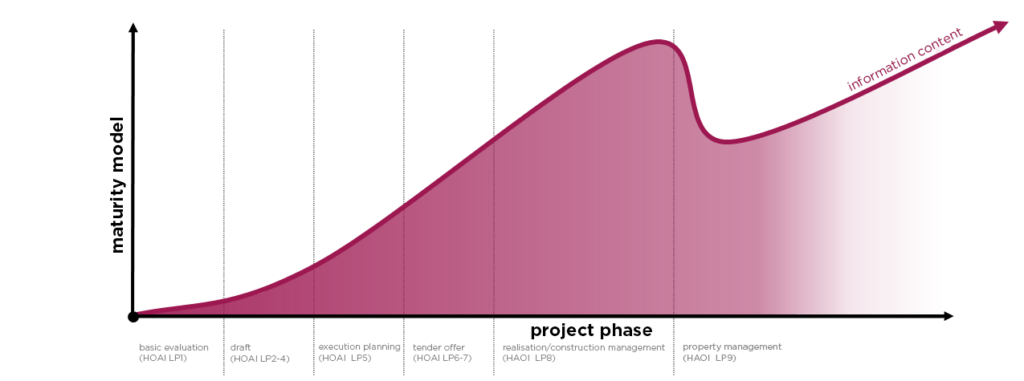

The development of the information content within a project model can take a different course than the geometric representation. In the preliminary and early design phase of a project the information content is usually quite low. The focus for the planners is initially on the geometrical configuration of the building. Some basic information may be included in the model, such as object dimensions (including floor surfaces), type definitions and perhaps some material surfaces, but the focus is typically on the geometric representation. From detailed design to tendering and implementation, the information content is constantly increasing (see Figure 2 below). There is no fixed rule here; however, the information content will eventually outweigh the geometric details. Certainly the information content of the models will reach a new level in the realisation phase, when model elements are embedded with manufacturer data of the products installed on site.

When it is handed over to the company, certain data is deleted from the model – especially information that is not relevant or necessary for facility management. In contrast to the geometry, which remains fairly stable after handover, the “digital twin” of the building is supplemented with new information during management.

Final word

The LOD is an important convention for the agreement of project results. It is a valuable standard for builders to clearly define their delivery requirements and is useful for contractors to determine the effort and costs required to achieve these outcomes. In model-based work it is necessary to distinguish between geometric and information content and to recognise that these aspects can be developed independently throughout the project life cycle.

Mark Baldwin

Author and BIM expert, Managing Director of Digital Insights GmbH and co-director of the Digital Construction course at the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts.