Posted by Tim Westphal

12/17/2020

Biological load-bearing systems translated into real architecture

Building Botany as a Construction Principle

If we look at the buildings that surround us, their load-bearing systems are often not apparent at first glance. Packed behind facades and under roof tiles, we can often only guess what lies behind them. Yet the basic structural principle of beam and support, for example, is much older than mankind itself. And long before the first clever master builder understood what compressive and tensile forces were, nature was already showing him how statics really works.

Interaction of biology and technology

When we walk with open eyes through our cities, parks and across meadows and fields, it is primarily trees that defy gravity with their trunks and spreading branches and stretch out toward the sun. But this tried and tested construction principle can also be seen again and again in the microcosm of plants and grasses. Adapting structures from nature, developing construction principles and transferring them into architecture is by no means new. In the recent history of construction, this is mainly summarized under the terms construction bionics and construction botany. Construction bionics aims to solve structural engineering tasks by applying biological principles. Popular examples include tree supports, as used at Stuttgart Airport, or as far back as 130 years ago, the support structure of the Eiffel Tower, which draw on nature. Building botany, in turn, is a construction method that combines living plants and non-living structural elements. This creates a composite structure of both grown and engineered elements. Popular examples include the living bridges of Meghalaya or the ancient custom of the so-called “dancing lime tree” or guided lime trees.

Building botany as a building principle

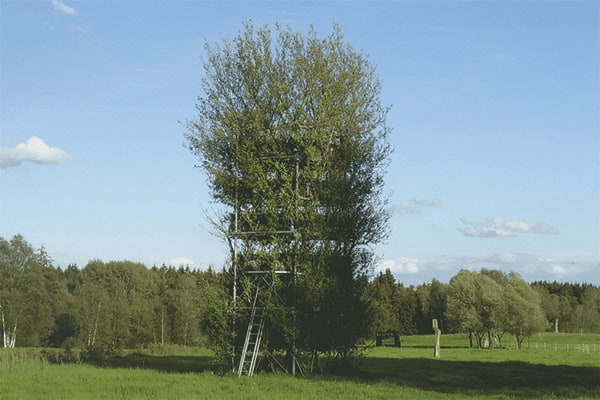

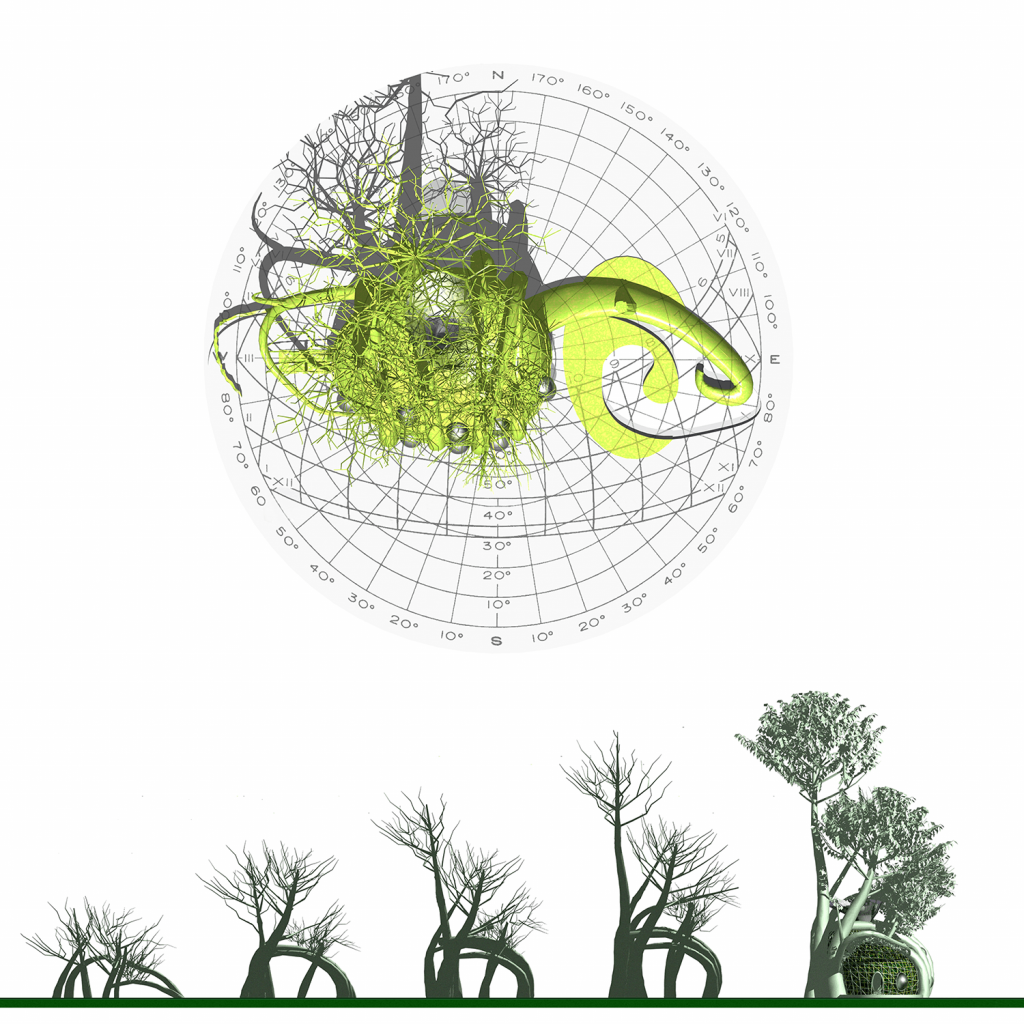

The living bridges like the dancing linden trees are very old applications of architectural botany. But in recent years, it is again finding increased influence in newer architecture. Prof. Ferdinand Ludwig of the Technical University of Munich has been conducting research in this field for many years. With his professorship for Green Technologies in Landscape Architecture, he is on the move in this unique sector of building, developing new, spatial structures and investigating their technical performance. He is also increasingly using hybrid connections between trees as the primary support structure and steel systems intelligently connected to the trunks for his projects. He has attracted much attention, including internationally, in recent years with projects such as the Building Botanical Tower and the Building Botanical Footbridge. Currently, he is working on the addition of tree trunks that are arranged on top of each other and connected to form an organism. His vision: to fuse buildings and trees – to create “breathing” houses, figuratively speaking.

Cultivated habitat from living trees

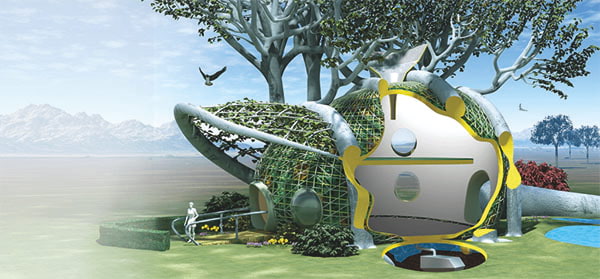

But also in the USA, for example, this important and by no means exhaustively researched approach to the fusion of nature, construction and building is being devoted to in depth. Not, for example, in the sense of heaped-up, funny hobbit earth huts, but quite seriously and with a great thirst for research. Mitchel Joachim and his cross-professional organization Terreform stand for progressive architectural approaches and are absolute lateral thinkers on a structural, social and cultural level. Joachim developed the “Fab Tree Hab” with Terreform.

Fab Tree Hab offers a sophisticated method to “grow” houses from living trees. This 100% living habitat is prefabricated using a multi-use scaffold. The CNC-milled scaffolding components can then be manufactured in a factory and delivered to the build (m)site, regardless of where the house is located. They are multi-way scaffolds to direct tree growth. Branches are repeatedly grafted on in parallel so that the structure grows rapidly. The space-creating scaffolding, the template of the building so to speak, is dismantled after this process is completed and can be reused for a new house. As in the case of Ferdinand Ludwig, the branches are interwoven here. A real-life example in the U.S. of tree weaving is the Basket Tree by Axel Erlandson. The resulting resilient structure, a continuous lattice frame of wall and roof, is protected with a protective layer of vines interspersed with greenery. Inside, a straw and clay composite protects against heat or cold from the outside. The structural comfort here is said to be equivalent to that of an adobe house.

Ecological architecture and high comfort

Independent of how close we are to the built reality with pilot projects and approaches of the building botanists Mitchell Joachim and Ferdinand Ludwig, both nevertheless show very impressively: sustainable and ecological architecture does not have to be associated with a loss of comfort or constantly destroy resources. The impact on the environment that we create with building botanical constructions is significantly smaller than with conventional building methods. In terms of the ecological footprint, it is therefore becoming increasingly important to advance building botany and, in addition, to think sensibly, wisely as well as regionally. True to the motto: “Think global, act local!”

Related links to our article

Article on welt.de:

Fab Tree Hab

- https://www.archinode.com/Arch9fab.html

- https://youtu.be/IdBbH2f

Current TV feature in the BR-Mediathek about F. Ludwig:

Ludwig lookout tower:

Source Portraits:

- Prof. Ferdinand Ludwig

- Mitchel Joachim https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mitchell_Joachim

Tim Westphal

Author and industry expert, specialized in architectural journalism on topics requiring explanation and complex building stories.